In MBA courses on Supply-Chain Management we often conduct an exercise that we call the Beer Game. In this game we set up a mock supply chain where there are lags in information flows for a single Retailer, Wholesaler, Distributor, and Manufacturer. Thus, we have a chain with four levels. The single retailer sees consumer demand, and this demand is variable in size. The Retailer then places an order from a single Wholesaler. The order takes 2 periods to reach the Wholesaler. The Wholesaler responds to the retail order, but that delivery takes 2 periods to move downstream. The Wholesaler then places an order from a Distributor that takes 2 periods to move up to that level, and so on. Thus, we have a system with variable demand and long lags between cause and effect.

The resulting system behavior is highly predictable in several respects. First, the variance in the orders placed grows as we move up the chain. As a result, doubling demand at the Retail end can end up as multiplying orders by 100 by the time the Manufacturer sees them. Second, the more the retailer over-reacts to a demand change, the worse the system will perform. As demand rises, the lags cause shortages at the retail level. If the retailer over-reacts by placing an order greater than demand, the Wholesaler is reacting to information that distorts actual demand. Each player then replicates this behavior to a greater or lesser degree and chaos ensues. The team that wins the game is almost always the one that has a retailer that never over-reacts. If the retailer only orders the actual demand, the problem is not solved, but the damage is typically minimized. The amazing thing about the game is that I know the outcome before we begin to play. It doesn’t matter if the players are under-graduates, MBA students, executives, or folks off the street, the outcome is always the same. Ultimately, the producer at the head of the chain has no idea what the real demand ever was, because the information that they received was distorted beyond recognition.

Equity markets are exactly the same even though they are completely the opposite. What the hell is that supposed to mean – you may ask. Let me explain. In the Beer Game, demand from the end consumer is the new information. The combination of human nature and the lags of fixed lengths built into the system work to create a setting in which the players making the biggest decisions, like the Manufacturers in a supply chain, only see highly distorted information. Thus, the behavior at the head of the chain bears no resemblance to demand at the other end even though the Manufacturer only produces with the intention of selling to the users at the other end of the chain.

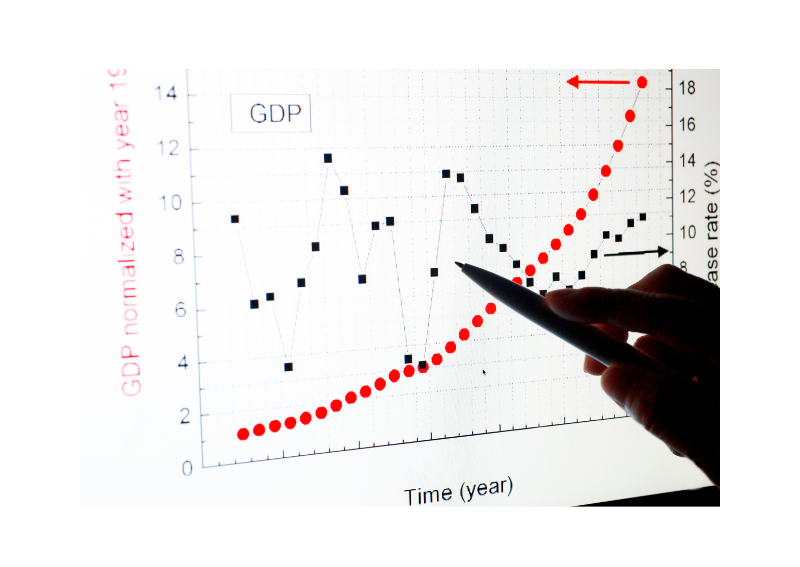

In an equity market information flows in the opposite direction. The producers of much of the new information and key players including large manufacturers, and governments are introducing that new information on a daily basis. In fact, they work to digest the information internally before it is ever released to the public. In some way, this runs our Beer Game in reverse. The Manufacturer (like Apple, Tesla, etc.) has perfect information about things like new products, financial performance, etc. They send this information downstream. The public sees this information with a short lag, but then over-reacts to it. In the Beer Game we consider a single retailer, but in the equity market we have millions of retail buyers. The parallel is that almost all humans over-react to new information, whether it flows upstream as in my supply chain, or downstream from a firm to shareholders. When everyone over-reacts to everything the stock price jumps about wildly even if the fundamentals of the firms under consideration don’t change at all. The end result of this systematic behavior becomes a mismatch between economic reality and equity prices. As a result, fundamental information like expected economic growth can appear to bear little resemblance to changes in equity prices.

Do not be misled here. Economic growth and corporate profits are definitely related at the aggregate level. Since 1800 the US economy as measured by real GDP has grown at an average rate of 3.7% per year. If you look at corporate earnings over the same period you will see that earnings stay remarkably close to 9% of GDP year after year after year. Thus, earnings tend to grow at roughly 3.7% per year (above inflation). This is not all that surprising. Earnings have to be a part of GDP. After all, the money has to come from someplace. If GDP doubles, output doubles, and if margins stay about the same, earnings have to double as well.

This raises an interesting paradox. If earnings growth (in aggregate) comes from economic growth, and the market is forward looking, then it would seem that expected economic growth will be related to the growth in the prices of the claims on those earnings – i.e. stock prices. However, this apparent connection is typically not evident in the data, especially over the short term. Let us highlight 3 reasons for this disconnection.

First, the time lines get out of sink. There is almost always going to be a lag between cause and effect. But the distortion we see in capital markets is likely to be much greater than what we see in the Beer Game, because in the game the lags are of fixed and known length, whereas in capital markets the lags can be both long, and variable. When this happens the correlation between events can get lost very quickly. Think about it this way. We may have very good reason to believe that A leads to B, like growth leads to profits. However, if the lag plays out over months or quarters and the lag can be of a different length each time, the pattern that we expect to see in the resulting data can get so distorted that it becomes invisible.

Second, since the market is forward looking, it is often the case that stock prices rise today because we expect earnings to grow tomorrow, and not because the economy is actually growing today. As a result, prices can rise before the earnings growth occurs. In fact, prices can rise while earnings are falling, if we expect this to turn around 2 or 3 quarters in the future. Thus, the earnings growth that shows up later appears to be uncorrelated to stock prices in place at that time.

Third, if we focus on the fundamentals, the stock price has to reflect both earnings and a discount rate. When earnings are growing rapidly, unemployment is low, and demand is high, inflation often follows. When this happens, the Federal Reserve starts to raise interest rates. As a result, the future earnings that you expect to grow, now have to be discounted by a greater factor. This can result in the present value of those earnings falling even as the expected earnings rise.

Consider this example. If we expect profits of $10 per period forever and we have a discount rate of 10%, the present value of this stream of values is $10/10% = $100. Now, if earnings jump by 5% but the discount rate rises from 10% to 11% because the Fed raises rates by 1%, we will have a present value of $10.5 / 11% = $95.45. Thus, if the investor expects both earnings growth, and a change in the discount rate, we can see falling prices with growing earnings even if no distortion takes place at all. Stated a bit differently, even if A leads to B, we may have mitigating factors, C, D, and E. The end result is that the appearance of the actual linkage between A and B is gone.

Another factor at play here is that if a stock market is highly (even if not perfectly) efficient, the future earnings growth is already “baked into” the current price. By the time most do-it-yourself investors see the evidence of earnings growth, it was already forecast by the professional analysts (and the firms) months earlier. Thus, the price has already risen by the time you and I figure out what senior management and all of “the experts” were thinking last quarter.

Finally, we have to always repeat that the stock market is an over-reaction machine. At the end of each trading day the news will report how trading that day was driven by news of this or that event. These noisy fluctuations disrupt the expected correlations between GDP growth (A) over the last quarter and price changes (B) over the same period. The way that this “Over-Reaction Machine” works is that having things go according to plan does nothing to prices because there is nothing new to react to. The main driver of price changes is the inflow of information that was not according to plan. This does not mean that there is no linkage between economic expectations and Values, but since the linkage to price changes is driven by surprises, the obvious link between Value and Price is hopelessly distorted.

As a result, while expected earnings growth is a great predictor of Value, it turns out to be a pretty crummy predictor of Price appreciation.